American Indonesian Chamber of Commerce

- HOME

- ABOUT AICC

- The History of AICC

- Major Initiatives

- Trade, Tourism, and Investment Program (TTI)

- Opportunity Indonesia

- Introducing Indonesia: Scholastic Ambassador Program

- Preventing A Lost Generation

- Comprehensive Indonesian-English Dictionary

- Sustain Sumatra

- 10 Year’s After: A nationwide public awareness program

- Support to Mandiri Craft

- Congressional Staff Visit

- Business and Cultural Programs in Dallas, Texas

- US-Indonesia Women’s CEO Summit

- Topeng Sehat: AICC Initiative Against COVID-19

- 2021 Shipping NYC Surplus PPE To Indonesia

- Board of Directors

- Membership Benefits

- FAQ

- Membership Registration and Forms

- EVENTS

- LINKS

- TRADE LEADS

- LATEST NEWS/COMMENTARY

- DOING BUSINESSS

- COUNTRY DATA

- BLOG POSTS

AMERICAN INDONESIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

Previous

Next

Your Trusted Partner

Since 1949, AICC has been your trusted partner in pursuing quality bilateral business objectives. Whether you are a US firm, Indonesian company, or individual researching the Indonesian market, AICC and its network of members in both countries stand ready to help make your enterprise a success.

Discover the power of our superior services

Discover our superior services

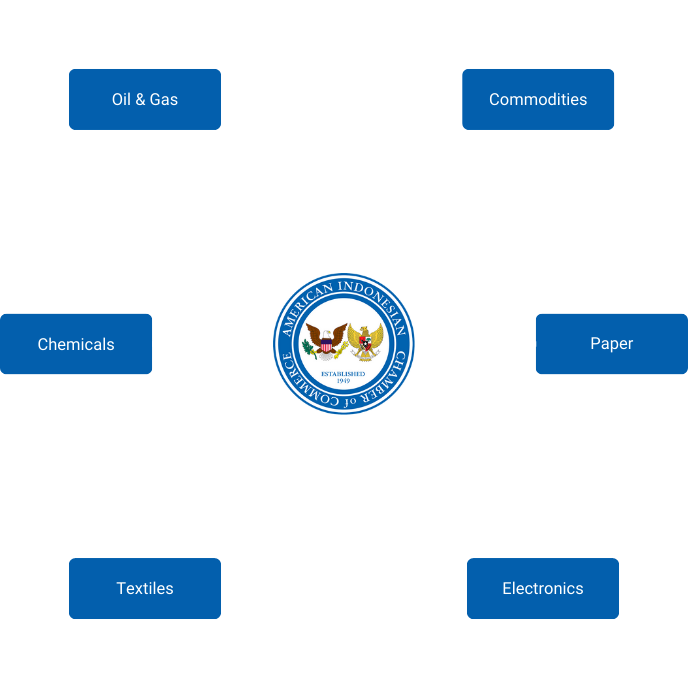

We provide high-quality, reliable and efficient offerings that provide great value. Our services also vary widely depending on your industry & business.

Wayne Forrest

President

Chambers of Commerce provide valuable resources, discounts, and relationships that help businesses save money and market their products. Joining a chamber of commerce can boost sales and improve a local business’ visibility and credibility.

Supported by Companies that trust our services

Your partner in international growth

Helping you expand your business across Indonesia.

Indonesia has a stable political system and a reform-oriented government that supports economic development and innovation.

Indonesia has a rich and vibrant culture, with friendly and hospitable people who are open to new ideas and opportunities.

Indonesia has abundant natural resources and a strategic location in Southeast Asia, making it an attractive destination for trade and tourism.

Bridging cultures and strategies

Improves communication and collaboration by reducing barriers and conflicts.